Reviewing: building rules

Before you can ask ClauseBuddy to automatically review documents, you must build one or more sets of rules. These rules can be managed through the Manage reviewing rules module on the home page of ClauseBuddy.

Review "categories"

When you first load this module, you will be invited to create a new review "category". As further explained below, you can create multiple categories — e.g., per legal domain, per type of contract or even per product/service that is being sold by your company.

When you click the green button, you have multiple options, further explained below:

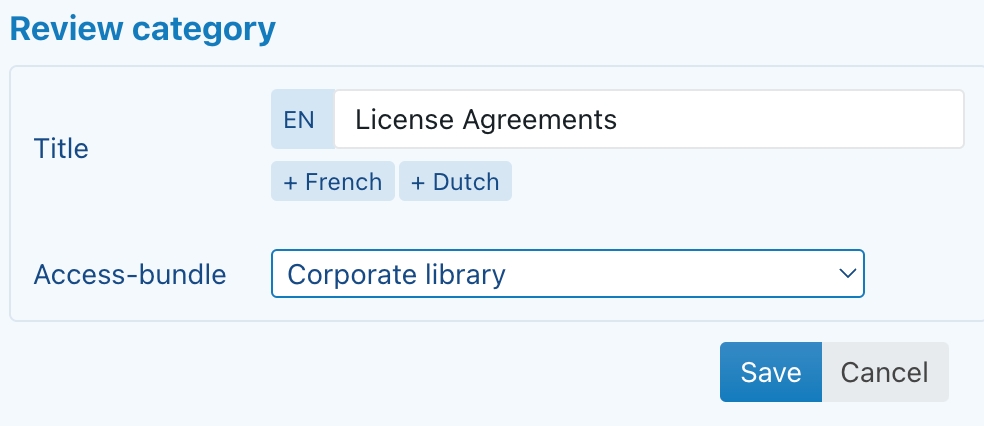

Each review category — however created — can be assigned a title (in multiple languages if necessary), and can also be made subject to access rights, e.g. to prevent that department X would be able to access the review rules of department Y.

Once a review category is created, you can update its properties (title and access-bundle) through the "..." button dropdown menu in the upper-right corner.

Creating a review category from scratch

When you click Start empty, you create a review category from scratch. You literally start from a blank sheet, and it's up to you to build up the rules from there.

Extracting rules from a text selection

A second options is to invite GenAI to extract rules from the currently selected text in your opened document: Extract rules from text selection.

Use this option if you already have some document in which rules are described — e.g. some kind of playbook that was developed several years ago in your company; or perhaps a list of rules and do's & don'ts that a client has provided you.

You simply select the relevant text part in that document, select Extract rules from text selection, wait for a few seconds, and you're done with a first version of your ruleset.

Checking out pre-made playbook samples

If you don't yet have a playbook/ruleset of some kind: don't feel bad. Few law firms have it (and usually only for some departments), and even for inhouse legal teams of large organisations it seems a minority.

Given this reality, and the fact that everyone's struggling with the horrifying thought of starting from a blank sheet, we've compiled a nice selection (currently more than 30) of playbook samples.

You can open them through the Download a playbook template option, and they look like this:

Essentially, they are Word files of between 1 - 10 pages, subdivided into different groups. Each rule starts with text in bold, and then the actual rule.

ClauseBuddy can automatically ingest Word-files that follow this structure, and convert them into a review category without your intervention. For example, the set above would lead to the following review category:

The most important task that you must execute as a legal team, is to take one of these samples, and then have internal discussions. From what we hear from the teams we work with, you will be amazed about how many internal disagreement you will have. You may think there is alignment within the team, but once you actually start to decide on the rules, you'll notice that many assumptions in everyone's mind are not necessarily shared across the team.

You'll also notice that the samples deliberately contain conflicting rules, and probably also too many rules. But — compared to starting from a blank sheet — most teams should be happy to go through the list, delete the rules that are not required for them, and tweak the remaining rules that are relevant for them.

Extracting rules from a document based on a sample

When you are done tweaking a sample, you can convert it into a review category by choosing Extract rules from current document.

As this process does not involve GenAI to interpret your content, you must respect a few basic constraints:

Subdivide your rules into groups.

Group headings must use MS Word style Heading 1.

Individual rules must:

consist of one paragraph (writing more is usually not recommended as the LLM may get confused by too much rules),

be formatted with MS Word style Heading 2

preferably start with a few words in bold, that contain the title of the rule (i.e., what is shown in the hierarchical tree, as opposed to the rest of the paragraph in plain text, which will be turned into the body of the rule).

The title of the document must use MS Word style "Title".

Other document elements (e.g., a TOC and some Introduction paragraph) are ignored.

If you start from one of the ClauseBuddy templates and just delete and copy/paste, the conversion will be flawless.

Extracting rules from documents with "outline levels"

If you have a document that was not based on a ClauseBase-sample, then either use the Extracting rules from a text selection option discussed above (which uses GenAI to interpret your text), or use a document that is created using outline levels.

This sounds fancy, but basically means to create a document where paragraphs have the proper outline level set. You can inspect this as follows for an individual paragraph:

It's probably easiest to use predefined Heading 1, Heading 2, Heading 3, ... styles to structure your document in a hierarchical way, because those predefined styles should already have the right outline level set. If you are using well-designed templates offered by your organisation, chances are that the main styles are also automatically at the right outline level.

Alternatively, you can jump to the "Outline" view — which is designed for quickly creating hierarchies of paragraphs — and then prepare a document in that view.

This is actually quite easy to do with the buttons that will appear.

ClauseBuddy can import paragraphs that have outline levels, with all paragraphs but the most inner paragraphs becoming "groups" and the inner paragraph becoming a "requirement".

General notes

Translations

Throughout the reviewing module, textual elements can be specified in multiple languages, if you are using an account on a ClauseBuddy server a in multi-lingual jurisdiction. However, to avoid screen clutter (in practice, in most legal teams, most reviewing rules are written in only one language) the boxes in which you can put other languages, are deliberately hidden on the screen until you enable Multilingual in the bottom-right corner.

The translations are mostly intended for your colleagues, and are not strictly necessary to complete. LLMs such as GPT can understand multiple languages, and will understand a Requirement written in French, and be able to apply it to an English contract.

Even so, it is often advisable to create translations. The reason is that the translation of some legal concepts can be dubious. In addition, when you give explicit instructions to the LLM on what to include in (or how to redraft) a clause, you may want to avoid the uncertainty associated with expecting the LLM to perform the translation for you.

Content length

You should be aware that one of the main limitations of LLMs consists of the length and complexity of the input you feed — i.e., both the content of your document and the rules you specify. While this is one of the primary domains of research, know that LLMs are very sensitive to the length, e.g. because doubling the input size causes the processing time to be four times as long.

Accordingly, you should try to find a balance between writing your instructions in a compact way, yet at the same time being sufficiently detailed for the LLM to understand the instructions. In this regard, you may want to treat the LLM as your average junior team member: if you first ask the LLM to read 50 pages of detailed legal instructions, and then ask it to review a 4-page NDA, it may deliver a worse job than when you had written a few key elements to look out for — similar to how your junior team member would react.

What must be specified, what can be omitted?

Taking into account the length constraints, you may want to skip content that you can assume the LLM already knows. The LLMs are trained on information available on the public internet, and it is often surprising what they know and do not know.

LLMs know a lot of facts, e.g. the capital of a country, what certain abbreviations (such as "GDPR" or "FDA") stand for, the functionality of certain product, etc. However, you should be aware that LLMs were trained up to a certain point in the past and will not be aware of facts that happened afterwards. If those facts would be important for the review, then you need to tell the LLM explicitly.

LLMs also have a reasonably good information about well-known legal documents for which many examples exist, e.g. NDAs and license agreements, particularly in large jurisdictions such as the United States and the United Kingdom. Conversely, LLMs will have only limited information available about contracts in small jurisdictions and niche areas of law.

Adding rules to a category

When you have create a category, you can add rules to them by clicking on the green "+" icon. Those rules can be one of the following elements:

A Group element allows you to add hierarchical structure to the other elements. You can organise your elements in groups, with sub-groups, sub-sub-groups, etc. any level deep. Groups are primarily intended for humans, the LLM doesn't even "see" them.

A Requirement is the most important element. It specifies a rule, and can optionally include conditions and actions.

Information extraction allows you to ask the LLM to extract information from a document (e.g., "What are the names of the signatories" or "What is the minimum order amount specified"), without any further judgement on whether it meets a certain criterion.

Literal text match allows you to perform a literal match on text that should be present (or, instead, must not be present) in the document, e.g. mandatory text that must be included in consumer contracts as per some statutory requirement. See the details in the subsection below.

A Condition element specifies that a certain condition must be met for a Requirement to become applicable. You can attach questions to a condition, which must be answered by the end-user before the review process can take place (e.g., "What is the deal size?" or "How many products of type X are being ordered?"). The end-user's answers to those questions can then be used by the LLM to analyse whether the condition is met, i.e. to decide whether or not the Requirement applies or not.

An Insight element provides background information for the LLM, e.g. to explain what your company's product "AlphaDogs" is all about, or how your support department will deal with requests in the weekend.

About the Literal Text Match

The Literal Text Match is provided as a specialised kind of requirement, because LLMs are very bad at looking for exact matches — they are experts at semantic understanding and grasping things, but are often "blind" for precise text being used or not.

For this reason, ClauseBuddy uses a classic (non-LLM) technology for performing literal text matches. As the name implies, a literal text matching is being performed.

In the following screenshot, the text "By submitting an Application Form, an Affiliate confirms that it has the consent of Prime Customer" will be searched in the document. Under the current settings, the rule is met when the text is present; and the rule failed when the text is missing from the document that is being reviewed.

ClauseBuddy always ignores consecutive spaces, and treats curly quotes in the same way as non-curly quotes.

When you check Find whole words only, ClauseBuddy will not find text fragments that are merely a part of a word. For example, when this setting would be active and you would search for "confidential", ClauseBuddy will not match on a word such as "confidentiality". (Of course this setting is irrelevant when you're searching for multiple words at once, as is the case in the screenshot above.)

When you check Case sensitive, ClauseBuddy will only match when the capitalisation is identical — for example, when you would be searching for "ACME", it will not match on "Acme" or "acme".

You should be aware of a few caveats when performing literal searches:

The matching is done in a very strict and literal way. This means that even a single character that's different will cause the matching to fail.

When you are reviewing a PDF-file, you must expect a level of "noise" being added to the document, because conversions from PDF-file are never perfect and conversions error may occur — particularly in documents with complex layouts, or documents converted from scans. Performing literal text matches within PDF-files can therefore easily go wrong, e.g. because characters are wrongly interpreted during the PDF-conversion, or because paragraphs are inadvertently split up in multiple subparagraphs/.

The matching is done on a per-paragraph basis. For several reasons, you must avoid trying to match on multiple consecutive whole paragraphs.

In legal documents, paragraphs will often have numbering prefixed. Sometimes that numbering will be automatic, often manual, or even a mix of both. Moreover, that numbering will often be slightly different — in some documents a target paragraph may have number 6.2, in other documents 5.1.

The longer you make your target text, the more likely it will be that even a single character will be different, so that the matching will fail. Searching for multiple consecutive blocks of texts will very often fail when performing a literal search, even though from a human perspective the text you are looking for seems to be present.

You must instead try to match on the real text substance of each paragraph, i.e. the text without the preceding numbering, and as limited in length as possible.

If you want to search for multiple paragraphs, then add multiple Literal Text Match rules. Do note that it is not currently possible to mandate that the paragraphs must be next to each other.

Performing fine-grained text searches at scale is an art on itself, often done by specialised software packages such as "e-discovery software", or even teams of dedicated developers. ClauseBuddy goes a certain way, but is focused on fast and simple searches, so don't expect it to compete with those advanced software packages / dedicated developers. For example, ClauseBuddy doesn't currently have the following features:

Support for different combinations, e.g. "paragraph A + B + C must be present, but it's also OK if C is replaced by D".

Support for "fuzzy matching", i.e. allowing small divergences, to make the matching less strict.

Searching for documents across hundreds or even thousands of files (*).

Searching across different document types than DOCX or PDF.

Adding a Requirement

Requirements specify a rule, i.e. something that must be met, either by being present, or instead not being presented, or having certain content. The associated Action will be presented on the screen, regardless of whether the requirement is met.

When you edit a Requirement, you will see the following screen:

In the Title box, you can give a title to your Requirement, i.e. a short explanation of your requirement in a few words (e.g., "Our liability must be capped" or "Confidentiality obligations must not exceed 5 years"). Don't make this too long, it will be the label that shows up in the hierarchy.

In the Contents box, you can give more details about the requirement, e.g. a description on what you expect to see in a contract or clause.

Additionally, you can add the following items through the green + Augment button in the bottom-right corner:

In Context you can specify information for your human colleagues — e.g. internal hyperlinks with more information, internal contact information, "war stories" from the past on how to deal with counterparties on this specific topic, etc. This information will not be submitted to the LLM at all (it will only be presented towards the human end-user), so do not feel constrained in length.

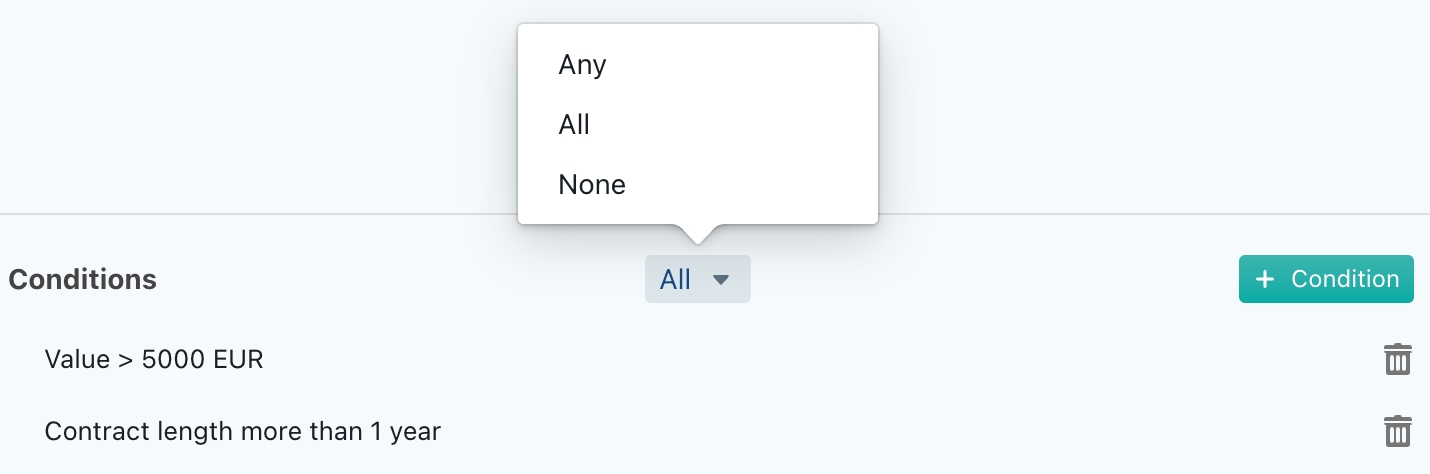

Through the Conditions you can specify Conditions for your particular Requirement to become applicable (see below for more information). When multiple Conditions are specified, you can also specify whether all those Conditions must be met simultaneously, or whether instead it is OK for only one Condition to be met, or whether instead none of the Condition may be fulfilled.

Through the Actions button you can specify adhoc Actions for your particular Requirement. More on that below.

Adding a Condition

A Condition allows to specify towards the LLM when a certain Requirement must be completely ignored.

Why should you want to use a separate Condition?

In principle, you can also specify condition-like elements in the Contents box of a Requirement, e.g. as a separate sentence after your description of what's required. However, it is not recommended to this extensively, due to the advantages of using a separate Condition.

Unlike conditions that you describe within the Contents box, conditions can have Questions associated with them, allowing the end-user to convey deal-specific information towards the LLM, as further explained below.

Components of a Condition

Similar to the other reviewing elements, a Condition has a Title box in which you can provide a brief description of your Condition (e.g., "Contract value more than 5000 EUR").

If the Condition requires more detail, you can also use the Contents box. (If it contains no contents, ClauseBuddy will instead only submit the Title to the LLM).

Questions

You can associate one or more Questions with each Condition. Those Questions will be presented to the end-user, and the answer(s) given by the end-user will subsequently be submitted to the LLM.

Questions are ideal for modulating your review, by including deal-specific information. For example, when a Condition would specify that a certain Requirement is only relevant when the deal value is more than 5000 EUR, but this deal value is not explicitly listed in the contract itself, the LLM obviously would have no way of knowing whether this Requirement is relevant.

You can create any number of questions, and ask different types of question (true/false, text, number, date, duration, currency).

Adding an Action

An Action will be presented to end-users, regardless of whether the requirement is met. For example, when a Requirement is "The applicable court should be French" and the associated Condition is "Deals relating to Product X", then you may want to suggest the end-user to:

Insert a clause from your Quality Library that stipulates exactly that.

Ask the LLM to rewrite the clause that specifies something different. You can then specify the writing instruction.

Add a comment in the document with predefined contents.

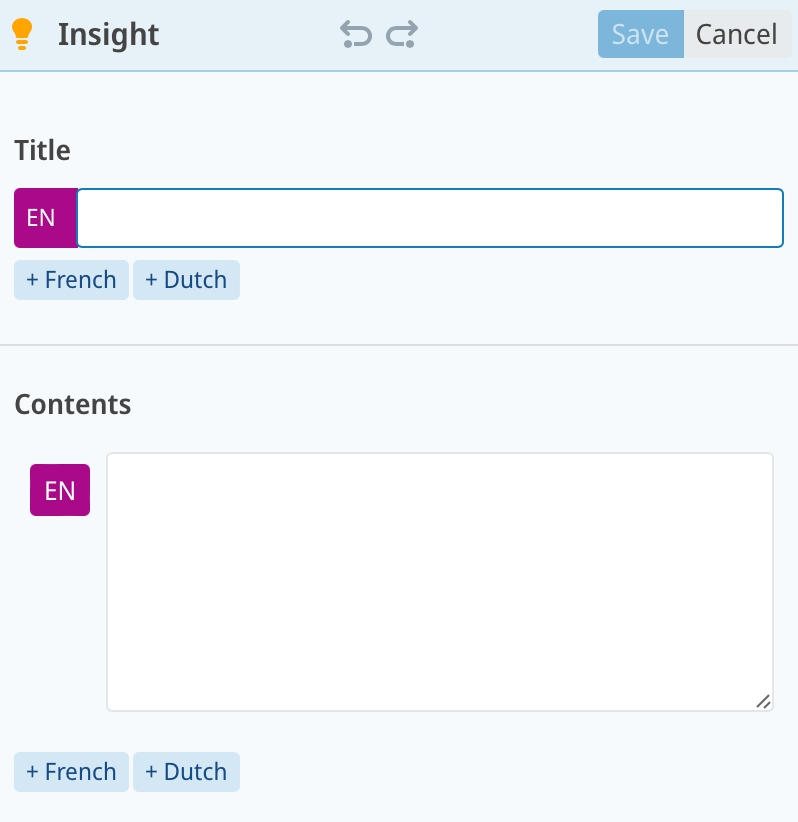

Adding an Insight

Insights allow you to provide background information to the LLM.

They are ideal for communicating information that is necessary for the LLM for assessing different Requirements. Instead of explaining certain internal concepts per Requirement, you are advised to create a single Insight that centrally lists that information.

An Insight only contains a Title and Contents box. As is the case with the other components of a Requirement, you can omit the Contents if it would not specify anything beyond the Title.

Review sets

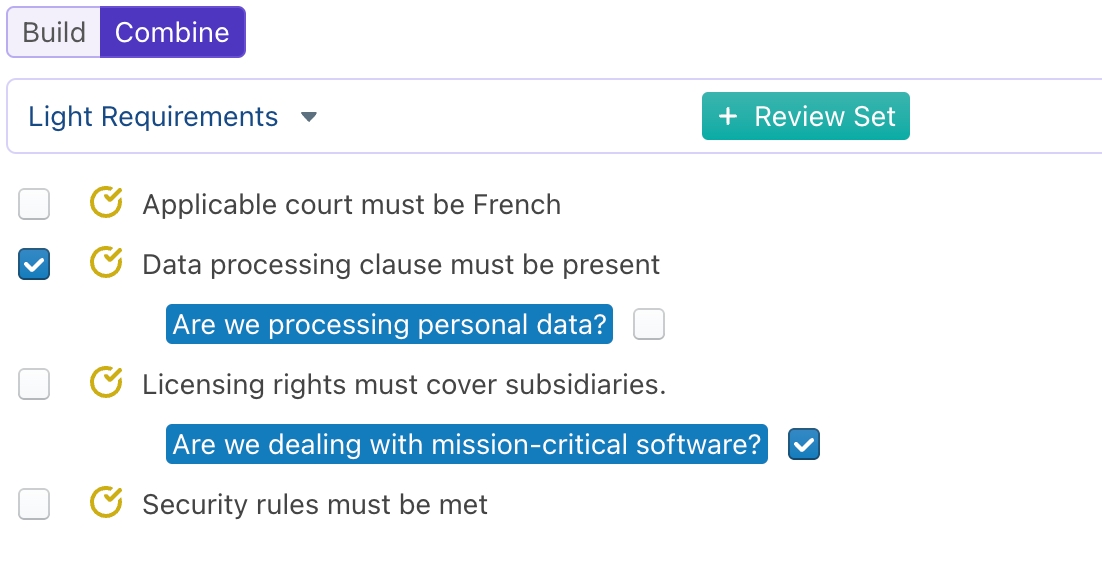

Once you have created several rules in a category, you can optionally create Review Sets by clicking on the "Combine" button.

The underlying idea is that not all your requirements will necessarily apply to every deal. Through Review Sets, you can specify which rules apply, and additionally pre-fill certain questions.

The end-user will then be able to specify the relevant Review Set when submitting an actual review request. For example, when licensing software, you may have 50 different rules that can theoretically apply, depending on the type of software being purchased, its mission critical nature, value, supplier, etc. Many of the more onerous requirements can probably be skipped when purchasing a low-value product, as opposed to purchasing an enterprise-wide multi-million dollar system.

If conditions have associated questions, then those can be optionally answered and stored within a Review Set. It is not necessary to answer all questions: questions that are left unanswered, will be asked from the end-user.

Only requirements that are selected will be submitted to the LLM.

Last updated